Earlier this year, my team published an article in Civil Service Quarterly posing the question: How good are we? – not as individuals, not as a team, but as an entire civil service. It looked at how international indicators of effectiveness might help us find the answer. The power of indicators, we argued, is not just in shedding light on our own performance but in highlighting where we can learn from others.

That focus on learning was an important feature of the OECD Public Governance and Centre of Government meetings I attended recently in Helsinki. They were also an excellent opportunity to discuss the benefits of international collaboration.

Behavioural insights

Firstly, we were able to share our experiences as early adopters of new approaches and discuss what we’d learnt.

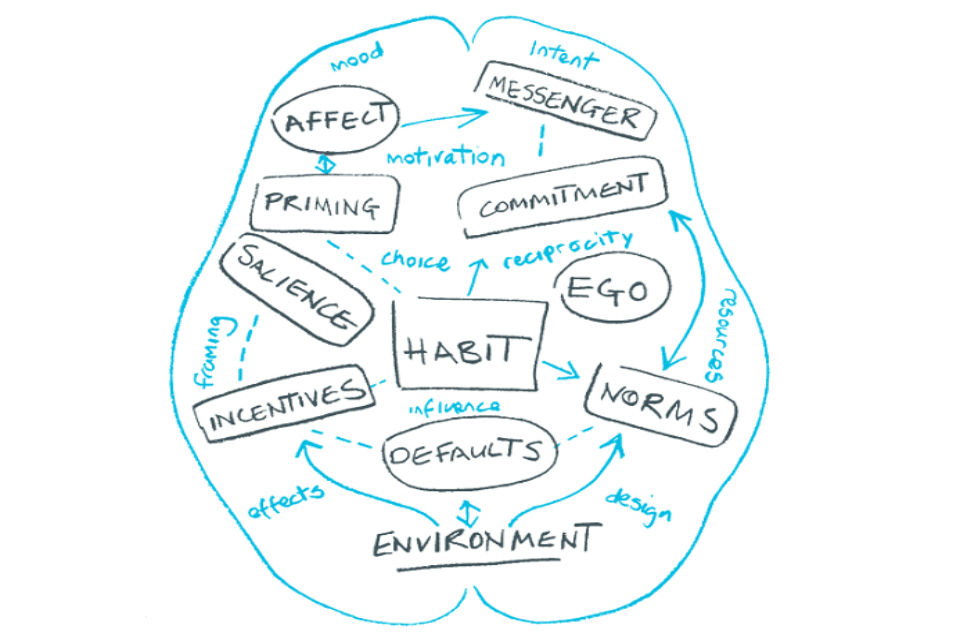

An obvious example is behavioural insights. In 2010, the UK’s Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) was the only one of its kind in the world. Now, all that’s changed, and we’re seeing the emergence of similar teams in governments around the world - from the White House to the German Chancellery. While others are drawing on our experiences, we are excited by the new possibilities for international collaboration, replication and the sharing of ‘what works’.

Another example is social investment. Other countries are particularly interested in the UK Government’s unique role in building this market They often want to know about innovations like Big Society Capital, the world’s first social investment wholesaler, and our hugely successful Investment and Contract Readiness Fund, both of which are now being replicated across the world. We know that we've got a lot to learn from others too, which is why we are active in the Global Social Impact Investment Steering Group (formerly the G8 Social Impact Investment Taskforce) and have supported the development of initiatives like the Global Social Entrepreneurs Network and the Global Learning Exchange, as well as working with the OECD to ensure we continue to learn.

Common issues

There’s much we can learn in other areas too; especially where countries are adopting new approaches to common issues.

One approach is to make greater use of challenges and prizes. In the US, challenge.gov recently celebrated its fifth anniversary. A White House blog describes how federal agencies have collaborated with more than 200,000 members of the public in more than 440 challenges, on topics from accelerating the deployment of solar energy, to combating breast cancer, and increasing resilience after Hurricane Sandy. The benefit is said to be that the government pays only for results, while the number and diversity of ‘solvers’ working on important problems increases.

Another example is using digital collaborative platforms:

- in France, they have created a website, Make it simple, for listening and co-creating solutions with users as well as simplifying administrative procedures

- in Estonia, The People's Assembly is an online platform for crowd-sourcing ideas and proposals to amend constitutional legislation

- in Korea, the mobile Community Participation App was developed to help citizens participate in deciding the policies that affect their daily lives at municipal and district level

Of course, there are examples of the UK using challenges and prizes (the Small Business Research Initiative (SBRI), the Public Sector Efficiency Challenge, the Business Impact Challenge and the new Longitude Prize), and collaborative platforms (DfID has been funding Amplify). However, some countries may have gone further in applying these approaches systematically. So, what else can we learn?

Collaboration benefits

At the recent meetings, we spoke about our proposals for new international indicators of civil service effectiveness. We feel strongly that our Civil Service should be able to demonstrate both to ministers and citizens that we are efficient, effective and improving our performance over time. Other countries recognised the unique role that well-designed new indicators could play and showed support for our proposals.

There are other areas where greater international collaboration could bring benefits. Every country needs to understand, across the full range of policy, whether what they’re spending public money on is actually working: what the most effective ways are of increasing educational attainment, of boosting local growth, or reducing crime. In the UK, we have a network of What Works Centres, putting the evidence into the hands of decision-makers in different policy areas. In Helsinki, we highlighted the opportunity for sharing, more systematically, what we know works and what doesn’t, and we are now exploring the potential for partnerships with other countries.

All in all, it was a useful few days in Helsinki.

I’m always reminded on such trips how similar the challenges are that we face. Keeping abreast of developments in other countries and thinking about how we might apply them back home remains a powerful tool for improving our own performance.