Hello again. It’s not long since my first blog, but I think enough has happened to justify an update.

One of my roles is ensuring the policy team in Defra get veterinary and science advice about exotic diseases. Although we do this mainly in preparation for such diseases, we really gear up when there is an outbreak and, as I am sure you are aware, last November we confirmed avian influenza (AI) in a duck flock in North Yorkshire.

Our processes

The team I lead have a number of roles during an outbreak.

The team I lead have a number of roles during an outbreak.

In this instance, the first indication we had was a private vet talking to our local Animal & Plant Health Agency (APHA) office about some ducks that had died on a large farm in Yorkshire. Because there was no other obvious reason for the deaths and illness, we could not rule out the cause being a notifiable disease, so an APHA vet was sent to examine the birds. In these circumstances, we ensure officials within the department and across government are kept informed about what is happening.

Once the APHA vet has looked at the birds, they ring my team to discuss their findings and together we agree a course of action. On this occasion, I took the vet’s call myself and, as we could not rule out an avian notifiable disease (which includes the viral diseases AI and Newcastle disease), we decided that samples should be submitted for testing.

My team act as the liaison between the local office, APHA, the labs and policy teams and the Chief Veterinary Officer to ensure everyone is kept informed. This time, unfortunately, the test results demonstrated that the virus that causes AI was present in the ducks on the farm and the disease was officially confirmed.

Such confirmation sets in motion an enormous amount of activity, locally, nationally and, in some cases, internationally. Apart from actions on the infected premises to humanely and safely cull the birds, staff have to visit other local premises, as well as any that are known to have links to where the disease has been confirmed. Internationally, there are potential impacts on trade, so our trade teams work with the embassies to provide reassurance where there are concerns over the disease risk.

Just as I was writing this, an outbreak of AI was confirmed in a chicken flock in Hampshire. Although a less severe form of the disease, it still presents challenges and has to be responded to quickly and efficiently. No two outbreaks are the same - I have experienced more than 20 - and there’s always something you can learn to meet ever- increasing expectations and scrutiny.

Using a Birdtable

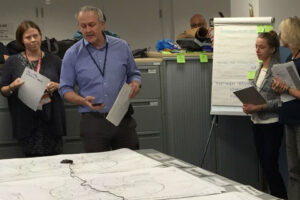

One of the ways information is exchanged within the National Disease Control Centre is via what we call the “Birdtable” - a regular meeting point for all policy, operational and communications partners involved in managing an outbreak. The idea of “birdtables” was introduced when the army was deployed to assist in 2001, and they are a very efficient way of quickly sharing information, raising concerns and identifying how they will be resolved.

On staff issues, we recently completed the mid-year review, which provides an opportunity to assess how careers are developing and what we can do to help staff reach their full potential. We are always facing new and unexpected challenges, so it is critical we develop staff who can respond to the new and unfamiliar diseases that could arrive on our shores at any time via the movement of people, vehicles, products and wildlife. As well as improving their technical knowledge, I look for opportunities for staff to respond flexibly and collaboratively, with an eye on future challenges. Even in times of financial constraint, it is always possible to find ways of developing people using shadowing opportunities and job swaps.

The team recently hosted some of our operational vets, one of whom was here during the outbreak. Although they would be the first to admit it was very different to their normal work, I am sure all 3 vets learnt a great deal about how we work and the range of veterinary jobs within government service and will be better informed when opportunities arise to develop their careers.

For more on how we respond to outbreaks of disease, have a look at the contingency plans.

Life away from APHA

As promised last time, a little more of what I do outside of work. For the last 2 years I have been a volunteer with Kent Search and Rescue.

Like cricket coaching it helps provide a balance to work, while providing opportunities to develop skills that can help in my job, such as teamwork, planning, resilience, use of technology, and so on. It’s not for everyone, but look into it if you’re interested.

There are over 30 lowland rescue teams in the UK. We are sometimes compared to the better-known mountain or cave rescue services, but what we do is very different and equally rewarding. The mountain rescue teams are usually looking for people who have got into difficulties while on an adventurous activity. Lowland rescue is more about locating vulnerable people who are missing, usually with inadequate clothing, overdue medication or depression. There is a lot of theory in determining likely places to search, as well as getting feet on the ground in all weathers and conditions.

As I say, the quality of life outside work contributes to effective and engaged delivery at work.